The Street Where CEOs Are Made: M&A Lessons from a Lemonade Stand

"On a good day, the sun sells for me. On a bad day, my plan does." - A hawker in Old Delhi

I went to Rani's lemonade stand as a thirsty customer. I left as her student - and frankly, questioning everything I thought I knew about M&A.

I've been through enough corporate acquisitions to know the process gets complex. Brilliant financial minds create intricate DCF models with multiple scenarios and detailed synergy projections. The analysis is often impressive - sophisticated tools, thorough methodologies, deep expertise.

But sometimes, in all that sophistication, the fundamental questions get lost.

It took a woman selling lemonade on a dusty Delhi street to remind me what smart capital allocation looks like when you focus on the essentials.

And yes, I know how that sounds. "Tech executive learns business from street vendor" - it's almost too neat, right? But what happened next genuinely changed how I think about M&A.

The Setup

Rani isn't just a lemonade seller; she's the undisputed queen of her lane. Kids gravitate to her cart drawn by the musical clink of ice against glass. Office clerks queue during breaks, mesmerized by the hypnotic swirl of her ladle as she mixes fresh lime with just the right amount of black salt. Aunties - and if you know aunties, this is the ultimate test - trust her to cut sugar without killing the joy.

Her stand is a bright yellow beacon, perfectly positioned to catch morning sun and afternoon shade. Everything speaks to optimization disguised as simplicity. Bottles arranged for maximum efficiency. Ice bucket at exactly the right angle. Even her plastic stool positioned to see every customer while watching her supplies.

That morning, between rushes, she was standing still, staring at the cart next door - Karim's chaat (spiced snack) stall - while wiping her hands on her faded but spotless dupatta (scarf).

"What's on your mind, Rani?" I asked, settling onto the sun-warmed plastic stool that had become my favorite seat in the city.

She sighed, the kind that carries the weight of an unmade decision. "Karim wants to sell his cart."

"And you're thinking of buying it?"

"Yes," she said, eyes lighting up. "If I buy it, I can sell mint lemonade and aloo (potato) chaat. One queue, two wallets opening."

Then she added something that made me put down my phone: "But do I get a bigger business - or just a bigger headache?"

In nine words, she'd captured what most M&A teams spend months articulating: the difference between growth and value creation.

I had a feeling this was going to be educational.

Act 1: The Logic of Expansion

"The best acquisitions don't change what you do - they amplify who you already are."

"Tell me more about why you want Karim's cart," I said, pulling out my phone to take notes.

She looked at me like I was missing something obvious. "My customers ask for snacks every day. 'Rani, do you have something to eat with this?' Every day, I send them to Karim. That's my money walking to his cart."

💡 Customer behavior analysis - she wasn't creating demand, she was capturing leaked value.

"Plus, the hostel boys (college students) come here twice - once for my lemonade, once for his chaat. If I have both, they come once and pay more."

💡 Revenue optimization through bundling - 150% increase in transaction value.

"And when it's really hot, Karim runs out of mint. When it rains, I lose customers but he still sells hot chaat. Together, we balance better."

💡 Counter-cyclical revenue streams - portfolio diversification using street food.

But what struck me wasn't her logic - it was her hesitation. She was asking the foundational question every CEO should consider: Does this make my core business stronger, or distract from what already works?

"Most companies spend millions on consultants to figure out what you just explained in three sentences," I said.

She laughed. "Maybe they should spend more time watching their customers."

Act 2: The Tin Box Revelation

"Cash is oxygen. Without it, you suffocate, no matter how profitable you look on paper."

"So what's stopping you?" I asked.

She reached under her cart and pulled out her dented tin collection box - an old Britannia biscuit tin with a cheerful child's face that had survived years of handling. She opened it with reverence usually reserved for family photographs.

Inside were two distinct stacks of money, organized with bank teller precision.

"These," she said, lifting the larger stack, "are coins from today. Cash from cups served. Real money that pays my rent."

Then the smaller stack: "And these? Promises for tomorrow. The school ordered lemonade for next month. The hostel boys pay monthly. Steady money - but still promises until cash changes hands."

💡 She was explaining bookings vs. cash collected without knowing the terms.

I nearly fell off my stool. The sophistication of what she'd described - timing risk in receivables - trips up seasoned SaaS investors.

My software executive brain was making connections. In Rani's world, buyers price young, fast-growing stalls based on their "promises per year" - what we call ARR in SaaS. But established stalls throwing off steady cash? They're priced on "coins left after the day's work" - pure EBITDA multiples. The parallel was stunning...but I pulled myself back to the scene.

"But what about Karim's business?" I asked.

"I need to see if his promises turn into coins. And..." she paused, studying his cart, "I need to check his pantry."

"His pantry?"

"His potatoes, oils, containers. That's money sleeping in storage. If his cash is stuck in rotting vegetables, what good is profit on paper?"

💡 Working capital analysis - better than most tech company due diligence.

She closed the tin with a soft click. "Tomorrow morning, we go talk to Karim properly."

I realized she hadn't asked if I wanted to come - just assumed I would. And honestly? I was already planning to clear my morning calendar.

Act 3: The Art of Looking Deeper

"Never buy what you can't inspect."

The next morning, the lane felt different. Quieter. The breakfast rush had ended, and the lunch crowd was still hours away. Perfect timing for the kind of conversation that required attention.

Karim spotted us approaching and his face lit up with nervous energy. He was a thin man with quick hands and careful eyes - the kind of person who noticed everything while focusing intently on his work.

"Rani! And sir!" he called out, immediately diving beneath his cart to retrieve a worn notebook wrapped in protective plastic. The kind of meticulous care that spoke to someone who'd learned hard lessons about preserving what mattered.

"See? Look here!" He opened it with obvious pride, pointing to numbers written in careful script. "Last month - very good profit. Revenue minus costs, all here."

I expected Rani to lean in and examine the figures. Instead, she stepped back, her gaze sweeping across his entire setup with the methodical precision of someone conducting an inspection.

"How much potato you keep in that crate?" she asked, pointing to a large container tucked behind his cart.

💡 Working capital tied up in inventory.

Karim looked puzzled by the question. "Maybe fifteen, twenty kilos? Depends on the day."

She nodded thoughtfully and continued her circuit. "Those hostel boys (college students) - they pay you when? Same day or later?"

💡 Receivables analysis.

"Ah, they pay every Friday for the whole week. Good customers, always pay."

"And Patel at the mandi (wholesale market) - you owe him money now?"

💡 Outstanding liabilities.

Karim's enthusiasm dimmed slightly. "Little bit. Maybe four, five thousand. He gives credit for good customers."

Rani continued her methodical examination. "Office people - how much of your business they are?"

💡 Customer concentration risk - the kind that doesn't surface until integration stress-tests relationships.

"Maybe sixty percent? They like the lunch special."

Then she got technical, pointing to various parts of his setup. "Show me your gas connection. Your storage. What breaks most often?"

💡 Infrastructure assessment - operational dependencies that financial models miss.

I leaned closer and whispered, "Why all these questions? His profit numbers look decent."

She paused her inspection and fixed me with a look that suggested I had much to learn. "Some carts show good profit on paper, but their pantry eats cash quietly. Karim might make money, but if his cash is stuck in bad potatoes or late-paying customers, what use is profit?"

Then came the line that hit like a perfectly aimed cricket ball: "Cash keeps you alive. Pretty numbers just make you feel good while you starve."

💡 The fatal flaw that kills more businesses than competition.

Her final question came as she studied his gas cylinder: "This connection - it's in your name?"

"Ah, no. My brother's name. But no problem, I use it."

Rani shrugged casually. "So what? Brothers don't fight over gas connections."

I stayed quiet, but her dismissal made me nervous. I'd seen enough family disputes in business to know that informal arrangements become major problems during stress.

It reminded me of tech acquisitions where the financial modeling was perfect but no one asked about the legacy database that couldn't scale to combined user loads, or the key APIs that were held together with someone's custom scripts. The unglamorous operational stuff that actually predicts integration success.

Act 4: The Weight of Borrowing

"Debt is like carrying extra weight - a little helps, too much kills."

That afternoon, the Delhi sun was merciless. The kind of heat that made even the hardiest vendors seek whatever shade they could find. Customers moved more slowly, lingering in air-conditioned offices before venturing out for their afternoon refreshments.

Rani was unusually quiet, mechanically wiping down bottles that were already spotless. I could see her mind working through calculations, weighing possibilities against realities. Her movements had lost their usual efficiency - she was somewhere else entirely.

"I like what I see in Karim's setup," she finally said, setting down her cloth with deliberate precision. "But I don't have enough cash to buy outright."

She paused, glancing down the lane toward a small shop where an older man sat cross-legged, surrounded by ledgers and counting money with the practiced ease of someone who'd been lending it for decades.

"I'll need to borrow from Sharma-ji."

The way she said his name - with a mixture of deep respect and careful wariness - told me everything about their relationship. Sharma-ji was clearly the lane's unofficial banker, the man who understood both the dreams and disasters of small business better than any formal institution ever could.

"Are you sure?" I asked, having watched too many debt-financed deals spiral into disaster. "He probably charges steep interest."

She turned to face me fully, her expression serious. "Debt is like carrying extra weight," she said, gesturing as if balancing an invisible load on her shoulders. "Little bit helps you carry more goods to market, earn more money. Too much weight..." she mimed stumbling, "you fall down."

💡 Capital structure optimization through physical metaphor.

Then she began counting off on her fingers, reciting what sounded like hard-won wisdom: "Sharma-ji taught me - even in bad week, my business should make double what I pay him. After buying new thing, I keep cash for three slow months."

💡 Interest coverage ratios and debt capacity management.

I had to smile. Here was street-level covenant management, distilled to its essence.

Her face brightened as she continued, "Besides, food business never really suffers. People always need to eat, always need to drink. Even when times are hard, they come for lemonade."

Her optimism was infectious, but I'd watched restaurant chains collapse during economic downturns - and seen enough 'recession-proof' businesses discover they weren't as countercyclical as their models suggested.

This discipline would have saved countless PE deals during the ZIRP years when cheap debt made everyone overleveraged. I'd watched firms learn this lesson the hard way when covenant breaches started cascading.

"What if something goes wrong?" I pressed gently. "What if the municipality suddenly cracks down on street vendors? What if the landlord doesn't approve the transfer?"

Her response was immediate, unwavering: "Then I walk away." She picked up her cloth again, resuming her methodical cleaning. "No deal is worth risking my lemonade stand. This," she gestured to her bright yellow cart, "this I know works. Everything else is just possibility."

💡 Walk-away value and financial discipline.

The certainty in her voice reminded me why she'd survived and thrived in this lane while others had come and gone. She understood something that many sophisticated investors forget: the value of what you already have is often worth more than the promise of what you might gain.

Act 5: The Mathematics of Tomorrow

"Future money isn't today money - too many storms can come."

The next day brought a different energy to the lane. Word had somehow spread about Rani's interest in Karim's cart - the kind of quiet buzz that ripples through tight-knit communities when something significant is about to shift. Vendors glanced over more frequently. Customers lingered a moment longer, sensing change in the air.

Karim appeared at Rani's cart just after the morning rush, fidgeting with a nervous energy I hadn't seen before. His usual careful composure had given way to the restless excitement of someone about to make a life-changing decision. He kept adjusting his cap, smoothing his shirt, checking his watch.

"Two years of my earnings," he announced suddenly, the words tumbling out as if he'd been rehearsing them all night. "That's fair price."

Rani set down the glass she'd been polishing and studied his face with the kind of attention she usually reserved for detecting the perfect balance of sweet and sour in her lemonade. The silence stretched between them, punctuated only by the distant honking of auto-rickshaws and the rhythmic chop of vegetables from nearby stalls.

"If your customers keep coming, costs stay same, mint prices stay normal - maybe fair," she said slowly, her voice measured and thoughtful. "But what if office building changes their lunch rules? What if someone opens better chaat (spiced snack) cart down the road? What if monsoon is bad this year?"

💡 Scenario planning and risk assessment.

She leaned forward slightly, her entrepreneur's mind clearly racing through possibilities. "How can I pay same price for money that comes in two years as money in my hand today? Tomorrow's money is worth less than today's money - too many storms can come."

💡 Time value of money, intuitively understood.

I watched this exchange with growing fascination. Here was someone with no formal financial training articulating concepts that trip up seasoned investors. I pulled out a piece of paper from my notebook, suddenly inspired.

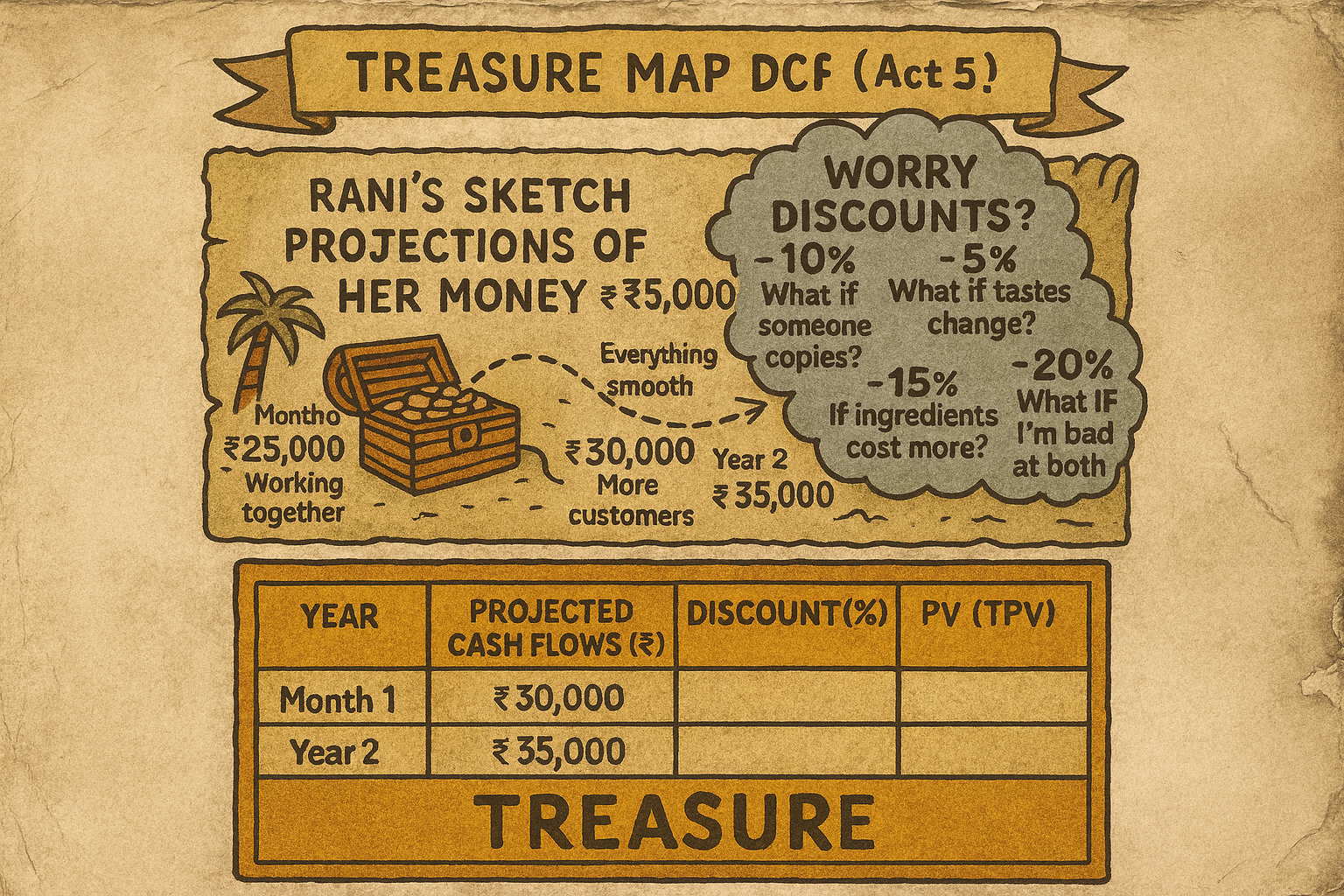

"Rani, let me show you something my finance teacher taught me," I said, smoothing the paper on her cart's small prep surface. "Draw yourself a treasure map of the future."

Her eyes lit up with that particular curiosity I'd come to recognize - the look of someone who loved learning new ways to think about familiar problems.

She took my pen and began sketching with the same careful precision she applied to everything else, her tongue poking out slightly in concentration:

Month 1: ₹15,000 (careful during mixing)

Month 6: ₹25,000 (working together)

Year 1: ₹30,000 (everything smooth)

Year 2: ₹35,000 (more customers)

"Now," I said gently, "think about all the things that worry you, and subtract for each one."

She nodded and began applying what she called her "worry discounts" with the methodical approach of someone who'd learned that optimism without caution was a luxury she couldn't afford:

"What if someone copies?" (-10%)

"What if tastes change?" (-5%)

"What if ingredients cost more?" (-15%)

"What if I'm bad at both?" (-20%)

💡 Discounted cash flow analysis from first principles.

What struck me was her intuitive Monte Carlo thinking - stress-testing multiple variables simultaneously. Most DCF models assume independent risks, but Rani understood that bad weather, new competition, and cost inflation could all hit together. Correlated risk factors that would make your base case and worst case uncomfortably close.

As she worked through the calculations, I watched understanding dawn on her face like sunrise over the lane. "See? Far-away money should cost less than close money," she concluded, tapping the paper with satisfaction. "More time for things to go wrong."

Then she looked up at Karim with that entrepreneur's gleam returning to her eyes. "But if your cart does better than I think, I should pay you more later. If it does worse, I pay less."

💡 Earn-out structures, naturally conceived.

Act 6: Crafting the Deal

"Best deals make everyone win."

Two days of thinking had transformed Rani's usual morning routine. Instead of her typical efficient movements, she worked with deliberate slowness, her mind clearly elsewhere. I'd seen this before - the careful consideration of someone who understood that the next conversation would change everything.

When she finally spread a fresh piece of school notebook paper across her cart's prep surface, smoothing it carefully, she had the focused energy of someone who'd worked through every angle.

"Some money now, you keep small piece of business, more money later if we do good."

She sketched as she explained:

40% cash now: "Shows I'm serious"

20% you keep share: "If we do great, you earn more than asking price"

40% over one year: "Only if we hit targets"

💡 Risk-sharing deal structure.

"Integration will be simple," she added with casual confidence. "First week, we just put carts together. How hard can it be?"

I admired her optimism, but having seen corporate integrations turn into months-long nightmares, I suspected she was underestimating the complexity.

Karim's brow furrowed as he studied her diagrams. "Why not just pay full money now?"

"Because if you believe your cart is good as you say, you make more money my way. If wrong, I don't lose my lemonade stand fixing your problems."

💡 Perfect incentive alignment.

My M&A brain was making another connection. This almost sounded like Transitional Service Agreements in corporate carve-outs. When a big company spins off a division, the parent keeps providing IT support, payroll, legal services - all the back-office infrastructure the new entity can't handle alone yet. The spun-off business pays for these services while building its own capabilities.

Here was Rani, naturally designing the same structure: Karim providing 'transitional services' - recipes, supplier relationships, customer introductions - while she built operational capabilities in the chaat business.

Again, I geek out on these parallels. But watching her intuitively arrive at solutions that billion-dollar deals use was genuinely fascinating.

Karim sat back, overwhelmed by the sophistication of what she'd proposed. This wasn't just a simple buy-sell transaction - it was a partnership structure that protected both parties while aligning their incentives for success.

The Handshake

What followed wasn't the immediate handshake of movies, but the careful process of turning ideas into reality.

Over the next week, Rani methodically worked through every detail. Landlord approval. Supplier meetings where she had to prove herself to vendors who'd known Karim for years. Recipe learning sessions where she took careful notes as he demonstrated the precise timing of spice additions.

When I asked about municipal permits, she waved dismissively. "Municipal people come monthly, we give them chai, no problem. Always works this way."

Her confidence in regulatory relationships was admirable, but I wondered if she grasped how quickly political winds could shift.

The breakthrough came on a Tuesday evening. Karim's biggest customer - an office manager who ordered for his entire team - casually mentioned how excited everyone was about "Rani and Karim's new partnership."

"People are already thinking of us together," Karim realized out loud. "Maybe this sharing idea is really good."

That evening, they sat across from each other at Rani's cart. She had prepared their agreement in her careful handwriting, every term laid out clearly. Sharma-ji and two other vendors witnessed - in this community, reputation was credit rating.

When she finished reading the contract aloud, Karim extended his hand across the narrow counter.

Their handshake was firm but brief - the grip of people starting something new together.

"Partners," Rani said.

"Partners," Karim agreed.

I'd just witnessed M&A strategy executed with more wisdom than most corporate deals I'd seen.

Six Months Later

The first thing I noticed when I returned to the lane was the sound. What used to be two distinct rhythms - Rani's ice clink and Karim's oil sizzle - had merged into a synchronized symphony that drew customers like a magnet.

The queue stretched further than ever but moved faster. Where customers once shuffled between two carts, now there was a single, flowing line.

"Welcome back, sir!" Rani called out, in constant motion - one hand reaching for lime while the other guided her ladle, eyes tracking Karim's chaat preparation. "Mint lemonade and samosa (fried pastry) chaat?"

The ease of that combination suggestion told me everything about the integration's success.

I watched their choreography: Rani calling drink orders while Karim plated steaming chaat, but when her queue grew, he'd seamlessly help with lemonades. When his oil needed attention, she'd plate samosas without missing a beat. Dancers who'd rehearsed a thousand times.

"How's the partnership?" I asked during a lull.

"Better than expected, though not as easy as I thought," she admitted, pointing to a handwritten sign: "Same Great Taste, Better Together."

"First month was messy - my customers confused, his suppliers not trusting me. But we figured it out. Karim's samosas with my mint lemonade? Lime cuts the oil perfectly."

A hostel boy (college student) approached. "Bhaiya, usual plate, but with Rani's special mint lemonade."

"Coming up," Karim replied, already moving while Rani prepared the drink. No discussion needed - just smooth execution of perfected routine.

Every rupee had found its purpose, every risk planned for, every decision validated by customers.

As a systems thinker, I realized Rani had naturally followed what I could now call the RANI framework - a mental model for M&A fundamentals: Revenue logic that customers validate, Asset diligence beyond financial statements, Navigating interdependent risks, and Incentive alignment from day one. Simple concepts, but I've watched Fortune 500 deals with perfect models stumble because they missed these basics.

What I Actually Learned

Watching Rani effortlessly suggest that lemonade-chaat combination, I realized something profound had happened.

She'd executed textbook M&A: strategic rationale from customer behavior, operational due diligence beyond financials, risk-adjusted valuation, creative deal structure. But she'd never lost sight of fundamentals.

The irony wasn't lost: trying to quench my thirst, I'd found the most practical business education of my life.

Her insights weren't despite her lack of formal education - they were because of direct exposure to reality. She understood customers because she served them. Cash flow because she counted every rupee. Operations because she ran them.

Corporate teams have sophisticated tools, but sometimes complexity overshadows questions Rani never forgot: Do customers want this? Can we execute this? Will this make us better? What could go wrong?

Whether evaluating $10 million or $10 billion deals, those fundamental questions remain the same.

Sometimes the best business education comes from unexpected places. Like a woman selling lemonade who understands that every transaction is a vote of confidence, every customer a teacher, every day an opportunity to build something better.

That's a lesson that complements any business education.

Have you found unexpected business wisdom in unlikely places? Or seen M&A deals succeed (or fail) based on these fundamentals? I'd love to hear your thoughts - drop me a line at [muktesh.codes@gmail.com].